Uncanny returns of the horror comic in the work of Hannah Berry and Gareth Brookes.

A paper given at the 5th International Graphic Novels and Comics Conference, The British Library London.

As forms of genre horror become ever more mainstream in Western popular culture, there is an increasing move away from forms of disturbing estrangement in favour of either a playing out of anxieties and the reinforcement of normative attitudes and expectations, or towards ironic reflection. Clever and funny but not scary. These are generalisations, but nevertheless, these appear to be the dominant tendencies.

I won’t attempt a historical context of anglophone horror comics, but it is a tradition that I find engaging. I tend to imagine a historical trajectory in the US, from pre code horror, to the re-emergence of horror themes in mainstream Marvel and DC titles, and the in the Warren titles (Creepy and Eerie.) while we had Misty and Scream in the UK, through to recent explorations of horror themes in the work of artists such as Charles Burns and Becky Cloonan.

I belong to a generation that aged with the comics. I read comics for kids, which became increasing aimed at older audiences. So those horror comics aged too.I was 12 when I discovered Swamp Thing, with the headline “Sophisticated Suspense” above the title, and no Comics Code Authority stamp. It went on to carry the promising warning For Mature Readers on the cover. These elements certainly helped to hook me as a reader, although it was Alan Moore’s name that hooked me too, as I had long since been a 2000AD and Warrior reader. But those days of kids reading comics, the 70s and 80s, are long gone, and We can only revisit those supposedly subversive pre code days with imaginary nostalgia for the young audience who devoured them in the early 1950s.

So, instead, I’d like to think about some things that might be thought of as contemporary horror comics, through Adamtine by Hannah Berry, and The Black Project, by Gareth Brookes. I’d like to talk about them as horror comics, and to think about what this might mean. Berry and Brookes offer strange, powerful and affecting returns for the presence of horror within anglophone comics. They recover the ability to disrupt the smooth surfaces of social reality.

So how do these books disrupt the surface of reality? How do they achieve a sense of discomfort, unease or dread? I would like to suggest that both Adamtine and The Black Project engage with what we can call the uncanny. These are distinct yet related manifestations of horror as something affecting, and as tied to forms of aesthetic experience, namely the uncanny, and connected to subversive possibilities of horror as a form of contemporary surrealism.

Berry plays on notions of doubling of the self, of the idea of the stranger, all taking place on that great space of modernity, the railway. The uncanny is present in the familiar locations, in domestic settings, offices, train stations. These spaces form the background for the carefully put together narrative, which demands attentive and close reading. It is very much in the tradition of powerful and concise short stories. Berry’s work is long enough to immerse readers into her world of dread and unease to which every panel adds, without diluting the narrative with unnecessary elements.

Anthony Vidler, in his book The Architectural Uncanny, writes “The contemporary sensibility that sees the uncanny erupt in empty parking lots around abandoned or run-down shopping malls, in the screened trompe l’oeil of simulated space, in, that is, the wasted margins and surface appearances of postindustrial culture, this sensibility has its roots and draws its commonplaces from a long but essentially modern tradition. Its apparently benign and utterly ordinary loci, its domestic and slightly tawdry settings, its ready exploitation as the frisson of an already jaded public, all mark it out clearly as the heir to a feeling of unease first identified in the late eighteenth century.” (Vidler p.3)

Vidler argues that this a domesticated outgrowth of the sublime, terror to be experienced in the comfort of the home. It is detectable in the tales of Poe and E.T.A. Hoffman. The motifs included the invasion of familiar spaces with alien presences and plays upon the doubling of the self. Vidler discusses this in terms of class insecurity, a bourgeois kind of fear. The comfortable setting in which these stories take place is itself brought into a degree of insecurity. It is an urban form of fear, arising together with new metropolitan spaces, transformed and intensified in Western culture by the terrible destruction of the World Wars. It emerges within Avant Garde practices as an instrument of defamiliarization, “as if a (Vidler says) world estranged and distanced from its own nature could only be recalled to itself by shock, by the effects of things deliberately “made strange.” (Vidler 8) This is the uncanny as an aesthetic category, as the “sign of modernism’s propensity for shock and disturbance.” (Vidler 8)

Berry uses a consistent formal device to structure her narrative. The story’s present is made up of rows of four panels arranged on black pages. Flashbacks to the recent past are made up of three panels on a white page. Without this separation, we would be lost in the changes between then and now, the subtlety of the narrative would shift from unsettling ambiguity to illegibility. Berry also makes use of the black of the page to indicate the presence of what we can think of as the book’s monster, a blackness that is a supernatural force of righteous and unyielding judgement.

We can also see here how the stable rows of panels are also occasionally disrupted. Such as this moment where one tall panel takes up all four rows in a flashback, a full length figure in a train toilet, staring down at the sink, ignoring his double in the mirror, then confronting it.

The image recurs towards the end of the book, when the identity of the protagonist, and his role in the overall story, is revealed. Over these two pages, we finally comprehend how he fits in to a cycle of bad decisions and unyielding punishment. The contrast between the two full length images, each of which is dotted below by an image of a mobile phone, to form a giant exclamation mark, generates a feeling of panic and confusion. My eye is drawn across the page in a frenetic jumble. The panels are much smaller than we are used to on the other pages, and they run down in two vertical columns on either side of a large panel, which reads as tall. The images are fragmentary, generating a sense of shock in the reader, and convincingly associating our confusion with the shock of the protagonist as he takes in the scene before him, piecing together the meaning of these fragments as we do, while the tall panels allow us to piece together the meaning of his decision. It is powerful and unsettling. These pages also play on doubling. There is doubling through repetition, through reflection. Through realisation, clues, lingering presences.

The narrative of The Black Project is also set against banal and familiar spaces, but rendered in a very different formal approach. The book has been made through a combination of lino prints and embroidery, achieving a unique visual sensibility. These techniques are used to depict strange and resonant images of nostalgic spaces, reinforcing the sense that adult readers are immersed in a world of childhood. The setting could be many places in suburban Britain in the latter part of the twentieth century, in a time before mobile phones and the internet. It is a world of net curtains and bad tv.

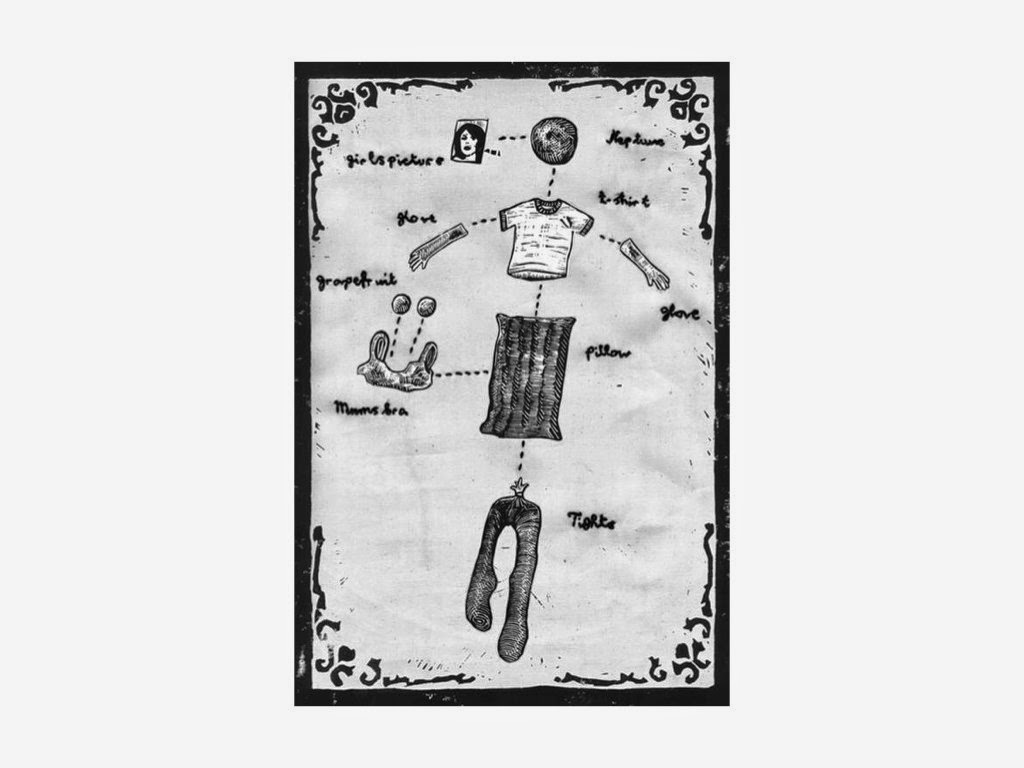

The Black Project focuses on Richard, a boy growing up in a dull suburban environment. His exact age is not disclosed, but he is somewhere between childhood and the more developed sexuality of an average teenager, in an uncomfortable hinterland where he is unable to talk openly about his desires. Alienated from the boring world of adults and from his own peers, he turns to a self created world of comfort and intimacy by making a series of girlfriends. The story follows his attempts to create and preserve a companion in the face of constant adversity. The great adversity faced here is the risk of discovery.

In The Black Project, we recognise the presence of Hans Bellmer’s poupees. This associate of the Surrealists constructed sexualised life sized dolls that still have a power to unsettle and disturb. The poupées were in part inspired by E.T.A Hoffman’s The Sandman, the story that is engaged with in some detail in Freud’s essay on the uncanny.

For Bellmer, these dolls were explicitly concerned with seduction and perversion, but also with the psychic shattering of the male subject. The eroticism was not just located within himself, but in the dolls, as if they were thinking and feeling subjects. This is the sense that is conveyed in the boy’s projection onto his dolls as actual girlfriends, not as dolls or substitutes. (Brookes has also shown versions of some of the dolls that Richard builds at the London Print Studio (2013) which reinforce the connection to Bellmer’s Poupees. ) For Belmer, these were representations for an adult to reflect upon nostalgia for adolescent desire. However, his dolls are also sites of resistance. In 1933, when the Nazi’s took power in Germany, he made the decision to give up any work that could be made useful to the state, however indirectly. This meant rejecting his background in engineering, and the beginnings of a career in design and illustration, which then led to his creation of the dolls. The poupées were made of wood, metal and plaster, with large ball joints making them infinitely posable. The dolls were photographed, and the original form of Bellmer’s doll work was a small self published book. The book contained ten photographs of the dolls, and a short text in which he speaks of his desire to recover “the enchanted garden” of childhood. (Foster 103) (He then published a set of eighteen images in the surrealist magazine Minotaure (Winter 1934-35) Foster then says that in a later text, “he locates desire specifically in the bodily detail, which is only real for him if desire renders it artificial - that is, if it is fetishised, sexually displaced and libidinally overvalued. Such is the “monstrous dictionary of the image”. (Foster 103) Foster argues that there is more to Bellmer than fetishism. These are not fixed but mobile configurations of desire. These are like sentences to be rearranged. Bellmer, he argues was making representations of mastery and control, but he also claimed he wanted to help people, to assist in their coming to terms with their instincts. Foster discusses this in relation to writings by Georges Bataille. (Foster 113) For Bataille, art’s origins in prehistory, and its childhood formations, are concerned not with resemblance, but by altération. This term refers to the formation of an image by its de-formation. And perhaps this is what Brookes is concerned with, both in terms of narrative content and the pictorial forms he employs. Might The Black Project be a process of de-formation?

There is a specific historical context in which Bellmer’s dolls are situated. Foster looks at them as the embodiment of Bellmer’s rejection of the Nazis, his resistance to them. They are attacks on the state, and upon his authoritarian father who embraced Nazi rule. Foster argues that Bellmer attacks Nazism through contesting the construction of normative masculinity with elements that the regime despised. The fascist body fears dissolution and otherness. Bellmer’s dolls posit a feminine with the construction of male desire. The fear of destruction and diffusion in fascist body imagery is manifested in the poupees. There are liberatory intentions in the critical exploitation of sexist fantasy and objectification. The dolls in The Black Project lacks the oppressive context of Bellmer’s dolls. But Foster argues that there is a primary surrealist politics: “to oppose to the capitalist rationalization of the objective world the capitalist irrationationalization of the subjective world.” (Foster 130) What a simple and effective way to remind ourselves of the subversive value of horror. Horror comics oppose the rationalisation of society with the irrational world of the subject.

There emerges a potential for these new horror comics to attack the normative frameworks of the expectations and demands of liberal democracy and capitalism. Can the uncanny question conventional and oppressive structures that enable class distinction and inequality? Does this kind of horror subvert social and economic repression?

Bellmer’s take on uncanny figuration is also included in a project by the artist Mike Kelley, whose exhibition and book The Uncanny developed from the collaborative work Heidi: Midlife Crisis Trauma Centre and Negative Media Engram Abreaction Release Zone, made with Paul McCarthy in Vienna in 1992.

Kelley began collecting images of figurative sculptures that possessed qualities he was interested in duplicating. When he was approached to make a work for the sculpture exhibition Sonsbeek 93 in Arnhem, Holland, he suggested an exhibition within the exhibition based on this collection of images. As the project developed, Kelley took his curatorial role seriously, leading to an accompanying catalogue, complete with his essay 'Playing with Dead Things: On the Uncanny', which was to become an influential text in the field of contemporary art. The exhibition has since been remounted in a larger form at Tate Liverpool in 2004, and an expanded catalogue produced.

In his essay, he makes it clear that the “uncanny is apprehended as a physical sensation” (26) in the manner he associated with an experience of artworks. He thinks back to childhood, to unrecallable memories of a confrontation between a ‘me’ and an ’it’, where the distinction between the two becomes confused. He says that these feelings “are provoked by an object, a dead object that has a life of its own, a life that is somehow dependent on you, and is intimately connected in some secret manner to your life.” (26)

He discusses Freud’s essay of 1919, writing that Freud distinguishes between the uncanny and the fearful in that the uncanny is associated with the bringing to life of what was hidden, bringing us back to something familiar. Freud cites Ernst Jentsch’s location of the uncanny in doubts as to whether or not a thing is alive, the possibility that a lifeless thing in fact being animate. He lists wax works, dolls and automatons among the objects that produce uncanny feelings. Kelley describes being struck by this, and how it corresponded to trends in art at the time of his first reading of the essay in the mid 1980s. And Among the images he compiles is Oskar Kokoschka’s doll of Alma Mahler, a fetish object that for years served as the focus of his desire, before it was discarded by Kokoschka and torn apart by guests at a party. However, Kelley tells his own version of the uncanny. He refers to, but deviates from Freud’s essay ‘The Uncanny’. Freud’s uncanny is not about lifelike objects, but about the return of the repressed, which is more the territory of Adamtine. Berry attacks a visual regime in which everything is depicted clearly, and fully explained, with no room for doubt or ambiguity, where we see everything constantly. Brookes is taking apart constructions of subjectivity and desire. The Black Project opposes stable forms of subjectivity often found in popular culture, while returning to the unstable manifestations of subjectivity often found within horror comics as a tradition. Just as Bellmer’s dolls expose fascist imagery, Brookes offers a similar exposure of our own culture of perfection and gendered fixity.

Both works are unflinching in forcing us to confront our own uncertain desires. These reinventions of horror comics reposition horror as a source of critical and disruptive reading experiences. These are sites of powerful and engaging disturbances inhabited by readers. Might such disturbances be aligned to disruptions of normative subjectivity, moral certainty and the fixity of social order?

In reconfiguring horror, they are able to disturb, performing a distancing and engaging form of alienation. Adamtine and The Black Project achieve their specific uncanny and disruptive power through an attentiveness to the narrative possibilities of the medium itself. They work towards a subversive alienating of the reader that has replaced the now lost value of comics as a corrupting influence upon the young.